Most people are mirrors, reflecting the mood and emotions of the times; few are windows, bringing light to bear on the dark corners where troubles fester. —Sydney J. Harris

I sat by the river with my coffee this morning. Felt my insides drawn out and superimposed upon the chops and ripples, waves, whorls and eddies, inconsistencies on the surface, reflective and responsive to even the subtlest of influence or intention, taking impressions from invisible forces like directions from a conductor. Galaxies of momentary stars glinting off the sun, pulsing brightly alongside one another, flashed for a flickering second and then were gone like shifting harmonies of light. Flowing.

A fish splashed up leaving a wake of bubbles and I imagined all the life within the depths of water. Not just this particular puddle, but all the liquid of the Earth. Aware of, affected by, every pull and stir on the surface, helpless but to absorb the effects. I wondered if they knew how much they were moving all the time. I felt water as the elemental layer between us and the universe below us and wondered what the skin of the sky must look like from above.

Water might just be the closest I’ve ever been to God, I thought to myself, absorbing the sermon being played out before and all around me. I feel we were probably once down there too, immersed in all that peace, but impudently managed to wriggle ourselves out, dry up and have spent centuries building ourselves up and away from it, trying to contain it, trying to control it, using it to suit our needs. We baptize our children in it. We bathe ourselves in it. We drink it to purify our systems, sooth ourselves with the sound of it. We use it to clean up the messes we make. Then we dump what we don’t want into it.

I watched debris float by on the current, pieces of trees mostly, voyaging downstream from where they’d lived to wherever they’d wash up or whatever they’d become. I know a guy in Costa Rica who collects driftwood from the beach near his house and shapes it into furniture. In the end, the death of one thing supports the life of another. If only we’d all paid attention to that simple truth before we disturbed the natural order: we don’t have to kill things to make use of them; every thing has its purpose, and death happens.

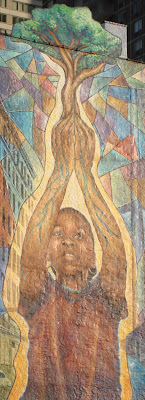

As I made my way home on my bike, I noticed the new Race Street Pier and decided this unexpected end-of-summer morning should be the last of it being a place I’ve wanted to go but had never been to yet. I started up the ramp and a large black man in a Security uniform yelled, “You gotta WALK your bike up there!” I stopped, looked at him and said, “Excuse me?” having heard him plain as day. “I SAID you gotta WALK that bike!” he bellowed sharply. “Oh, I didn’t know,” I told him, paused to dismount my bike and said, “and GOOD MORNING,” with a sweet smile disguising a terrier snarl.

I walked my bike to the end of the pier and took a look around.

I was watching a large bird with a long, pointy beak surf the current when the man in the uniform came walking up beside me and asked, “Did you think I was mean?”

A little bit, I told him. “You could have said good morning first.”

He apologized and extended his hand, which I shook firmly and gratefully. We stared out at the water. “You off from work today?” he asked after a pause.

“No,” I shook my head. Seeing his confusion I added, “I work a little differently than most people.”

“ What do you do?”, he asked.

I teach yoga, I told him.

“Oh, like the exercise,” he nodded in recognition.

“More or less,” I said.

He stared at me.

I explained that yoga’s more a way of life than exercise. The exercise is what we yogis call practicing, which really is studying ourselves to clear away the stuff that isn’t good.

“A lot of people don’t study themselves at all,” he said thoughtfully after a moment. “Why do you think that is?”

“Probably they’re afraid to look,” I told him.

“So, you, as a teacher, you think you a hundred percent clear?” he asked.

“Nah,” I shook my head, “I don’t think that. But I try. I think there are probably very few people who can completely clear themselves to a point that they’re one hundred percent connected to Divinity all the time.”

He thought for awhile and said, “A pastor once told me that for all the trying people do to get themselves right with God, there’s always something they hold onto keeps them from it.”

“Well, no matter how clear we get, we always have to rub up against everyone else and their stuff. Whatever extent they’re connected to God, they’re connected to us in ways that affect us and so we react and have to keep on revising.”

“You a pretty intelligent young lady,” he said with a steady, eyebrow-knitted stare and grew quiet.

“Ever notice the way water affects humans when they close to it?” he asked after a silence.

I nodded and smiled. “I think we hear its message of cause and effect. Every little intention shows up in the water.” I said, jutting my chin toward all the movements happening at once.

“I think it’s cause we made up of 75 percent water and we feel that when we get close to it,” he said gesturing to himself and his own wateriness. After a pause: “God sure knew what he was doing.”

“I know exactly what you mean,” I said.

The cycle continues...

The cycle continues...